Whereas Mississippi Delta Blues is a well-known and recognisable form of the music, there is a lesser-known style that might well have slipped under the radar of some folks. It was in the North Mississippi counties of Marshall, Panola, Tate, Tippah and Lafayette where virtually the only work to be found was in the lumber industry and the small farms that The Mississippi Hill Country Blues originally took shape.

Their music is deep Country Blues with a driving rhythm, hollered singing over a basic chord sequence, heavy, riffing, hypnotic guitar, unexpected and irregular song structures and all the feeling you could wish for. The towns of Holly Springs and Oxford, less than 60 miles from Memphis, Tennessee are considered to be at the centre of Mississippi Hill Country Blues.

The most familiar Hill Country Blues musician was the massively influential Mississippi Fred McDowell, with artists such as Bonnie Raitt and The Rolling Stones acknowledging McDowell’s work. Raitt developed her slide guitar technique from listening to his recordings and recorded his songs, while The Stones laid down a rocking version of his classic “You Gotta Move” on the “Sticky Fingers” album.

McDowell was born in 1904 in Rossville, Tennessee to farmers Jimmy McDowell and Ida Cureay who both died while Fred was in his youth. He worked on a farm, taught himself to play guitar, played local dances until he left home at 22 to hobo as an itinerant musician playing suppers, picnics, house parties, fish fries and dances in Red Banks, Lamar and Holly Springs in the Mississippi Hill Country, before settling in Como to work as a farmer, continuing to perform at weekends. He married singer Annie May Collins in 1940, who stayed with him until the end. They had one child.

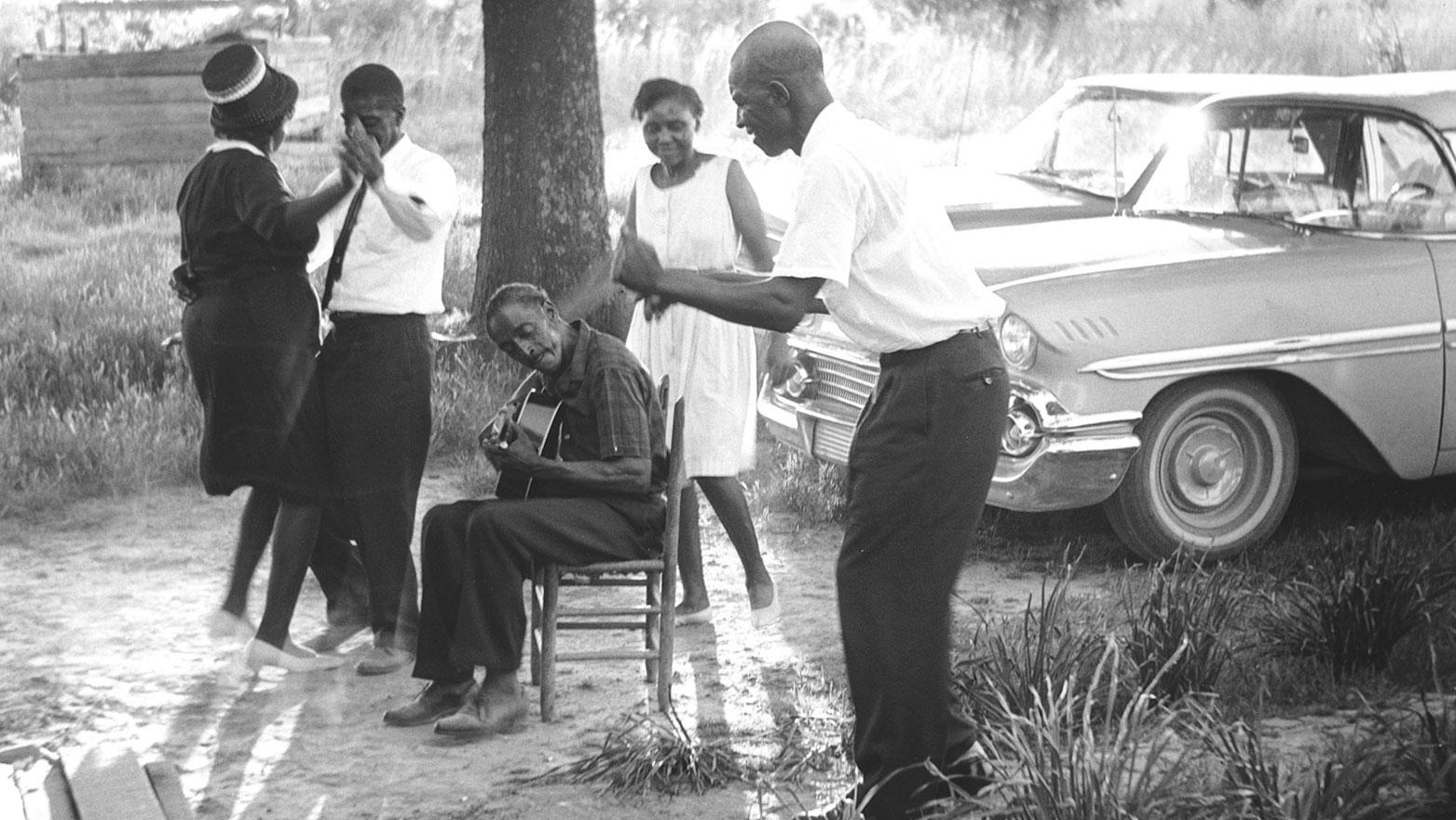

That’s where he was found by Alan Lomax in 1959 who was the first to record him, but McDowell’s breakthrough didn’t come until four years later, when he was 60 years old and Chris Strachwitz went to his Como home to record him for those good guys at Arhoolie. They recorded two albums in fairly short order, bringing Mississippi Fred McDowell the attention he deserved. He played at Blues Festivals throughout the UK and Europe and appeared in the films “The Blues Maker” [1968], “Fred McDowell” [1969] and “Roots of American Music: Country Urban Blues” [1971].

I was fortunate to see and hear him when he first came to the UK as part of the 1965 American Folk Blues Festival – God Bless Horst Lippman and Fritz Rau – and he was extraordinary.

His subsequent recording output was prolific with releases on Vanguard, Testament, Milestone and others as well as more on Arhoolie.

He was mostly inactive during 1972. He died that year in Memphis and was buried in Hammond Hill Church Cemetery in Como, Mississippi. He was 68.

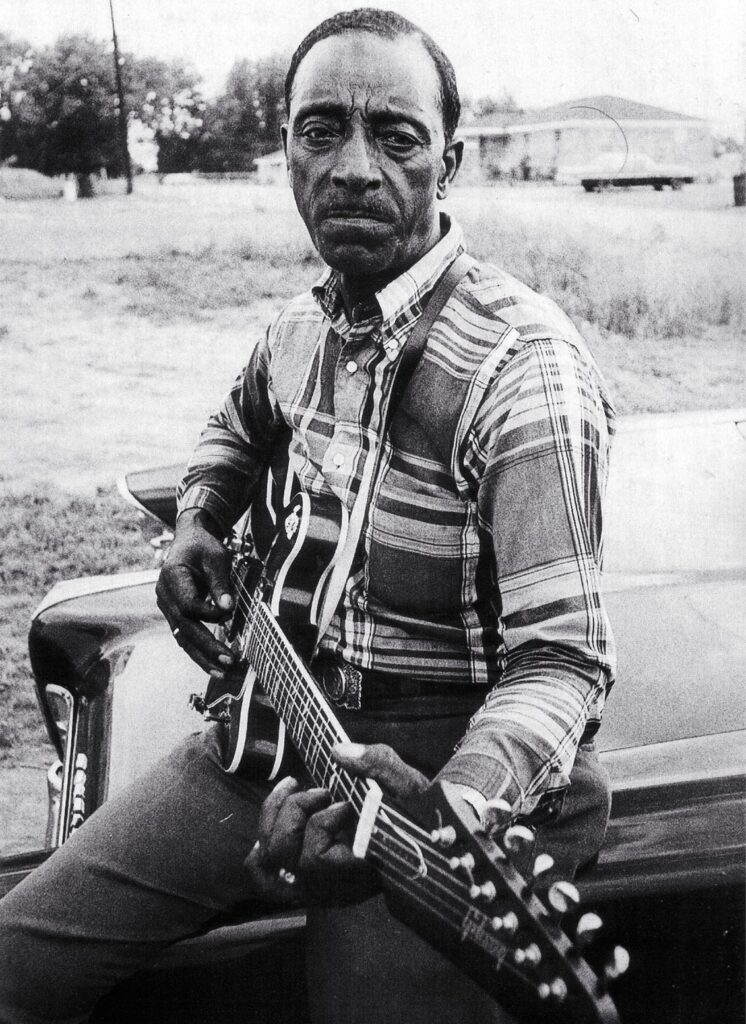

R.L. Burnside was born in the heart of Hill Country Blues territory in Oxford, Mississippi in 1926. He learned to play guitar aged 7 or 8 years old by listening to Mississippi Fred McDowell, and began playing Juke Joints while in his teens though he didn’t get to record until the late 1960s when he appeared on an Arhoolie anthology. In the late 1940s he moved to Chicago, where he became a Maxwell Street regular, but Chi-Town didn’t treat him well: his father, two brothers and two uncles were reportedly all murdered within the span of one year. Three years later R. L. moved back South, married Alice Mae Taylor in 1949 or 1950, a union that eventually produced thirteen children and thirty four grandchildren. It is said that R.L. was convicted of murdering a man in a crap game in the early 1950s and sent to Parchman’s Farm where his boss arranged for his release after 6 months as his skills as a tractor driver were required.

R. L. Burnside toured Europe in 1971, the first of several such tours that saw him record for Swingmaster in Holland and Arion in France. The last 20 years of his life were the most musically productive with regular tours and festival appearances and several recordings including his “Bad Luck City” for Fat Possum Records in Lafayette County, Mississippi. He appeared in the film “Hill Stomp Holler” 1991 and, intriguingly is said to have become an influence on the Garage Rock movement and he even opened a show for The Beastie Boys.

R.L. Burnside died of heart disease in Memphis in 2005 at the age of 78. His sons Duwayne and Gary, and grandsons Cedric, Kent and Cody, all became musicians. After his death R.L. won no less than four W.C. Handy Awards.

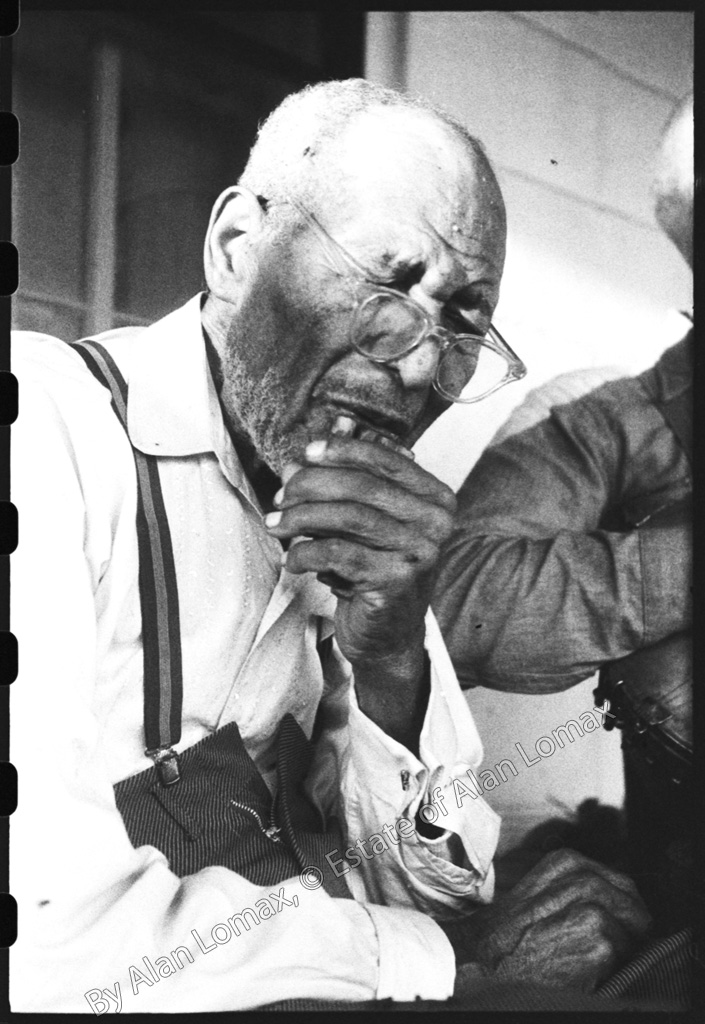

Sid Hemphill, the musical patriarch of Mississippi Hill Country, was born in Como, Panola County, in 1878 according to State records, or in 1876 according to Sid himself. The son of a slave fiddle player he was a blind multi-instrumentalist – banjo, guitar, piano, violin, organ, cane fife and more – and songwriter who hand-crafted instruments.

A local string band leader described him to Alan Lomax as “the boar-hog of the hills, the best musician in the world” and apparently Lomas found little to argue about with that, promptly high-tailing it down to Mississippi in 1942 and recording twenty two of Hemphill’s performances as well as an interview. Lomax was to make a similar trip in 1959.

Sid never recorded commercially, although the Lomax recordings have been widely-circulated. Among his many achievements, he wrote the song “The Eighth of January” which was taken by Jimmy Driftwood and became the hit “The Battle of New Orleans” for Johnny Horton.

Sid Hemphill is honoured with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail. He died in Senatobia in 1967, aged 89 years old or 91!

Sid’s daughter was Rosa Lee Hill, born in Como in 1910. She was briefly married to a Napoleon Hill, whose name she kept as well as all the income from his book that she assisted him in writing, “Think and Grow Rich”, on the basis of a pre-nuptial agreement signed when he was broke. She went on to write her own book, entitled “How To Attract A Man and Money”.

She recorded the album “Rosa Lee Hill and Friends” for Fat Possum Records, music that was in the North Mississippi tradition. Her song, “Bullyin’ Well”, recorded by Lomax, has been released several times over the years. Rosa Lee Hill died in Senatobia in 1968, aged 58.

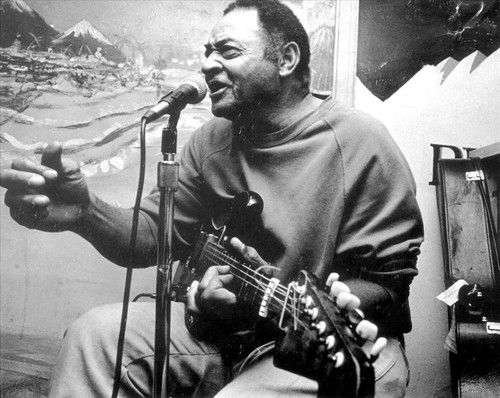

The man often referred to as the perfect example of Hill Country Blues was born in 1930 in Hudsonville. His childhood friend, country and rockabilly star Charlie Feathers described him as “the beginning and end of all music”, a statement that is engraved on the tombstone of the singer and guitarist referred to, Junior Kimbrough.

Born David Kimbrough, he first picked up guitar as a child, influenced by the playing of his father, who was a barber by profession. Junior said that his main influences were Mississippi Fred McDowell and a certain Eli Green, said to be a dangerous Voodoo man!

In 1986, Junior travelled to Memphis to record for Goldwax, who then decided not to release the tracks as they were “too country”. These recordings eventually saw the light of day in 2009 on Big Legal Mess Records.

Junior Kimbrough was a popular Juke Joint owner, with his debut album “All Night Long” recorded in 1992 in his Junior’s Joint, previously a church, in Chulahoma. This was the album, on Fat Possum, that brought him to wider attention and a 4 star review in “Rolling Stone”. His bass guitarist was R.L. Burnside’s son, Garry. His drummer was Junior’s son, Kent ‘Kenny’ Kimbrough. His last two albums “Sad Days, Lonely Nights” and “Most Things Haven’t Worked Out” were also recorded in his Junior’s Joint, which became a place of pilgrimage whose visitors included Keith Richard, Iggy Pop and U2. After his death, his Juke Joint continued successfully under the management of his sons, Kinney and David Malone Kimbrough, until it was destroyed by fire in 2000.

Junior featured in the film “Deep Blues – A Musical Pilgrimage to The Crossroads” [1992] filmed in one of his Juke Joints, Chewalla Rib Shack, east of Holly Springs.

Junior Kimbrough died of a stroke followed by a heart attack in 1998 and is buried in the grounds of The Kimbrough Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, near Holly Springs. Purported to have 36 children, he leaves more than simply the legacy of being one of the leading figures in Mississippi Hill Country Blues.

Jim Simpson