The Henry’s Postbag received an interesting note from a British bluesman living in France. It read, “My name is Giles Robson and I’m writing an article on Memphis Slim. I’ve been reading your Bluesletter with interest, especially regarding Willie Mabon and Mickey Baker and their relationship with Memphis Slim.”

What Giles modestly failed to mention was that he is a blues singer and harmonica player of some renown, the first UK/European bluesman to record for Chicago’s respected Alligator Records. This album, “Journey to The Heart of The Blues”, was instrumental in Giles becoming, in 2019, the only British bluesman, except for Eric Clapton and Peter Green, to win a Memphis Blues Music Award.

We chatted, and he wrote the following for the Bluesletter:

During a very hot day in May 2018 the relationship with my then partner and the mother of my children came to a halt and I had to suddenly make other living arrangements. Not unusual in the life of a musician, my chaotic work schedule and my stubborn refusal to give up my life in music and retrain in an alternative more respectable profession had worn her patience out, and I was out!

Her house, the family house, having a central London address and a price tag to match, was based in an area that had an impossible to penetrate “financial forcefield” around it in terms of affordable living. In fact the majority of London did, so I decided to beat a retreat to France and lick my wounds and just have somewhere to live that was both salubrious and within my reach financially.

I had, many years previously, purchased a tiny 26 square metres studio apartment in a medieval village on the coast of Brittany and it seemed like the only good option. It turned out to be the perfect option, and ironically was cheaper to get back to London either by boat or plane than it was, for example, to take a return train journey from London to Plymouth.

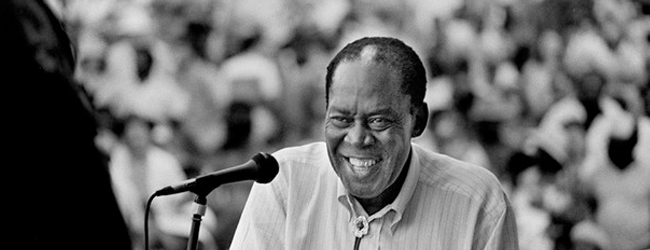

It was whilst in France that a friend, by way of consolation, sent me a photograph of blues piano legend Memphis Slim. His message was along the lines of – “Don’t worry, Blues Musicians seem to do well in France!” Slim certainly looked like he had done VERY WELL!

Standing next to his own Rolls Royce on a posh Parisian street dressed in aristocratic evening wear and with the S on the Slim of the autograph struck through with two lines to make it into a dollar sign. As Zero Mostel’s character in Mel Brooks’ movie The Producers manically shouted, when spotting a Roller outside a posh restaurant across the street from his crummy office, “If you’ve got it, flaunt it!” Slim looked like he had it and by all appearances was incredibly adept in flaunting it.

Memphis Slim had been omnipresent in my life since my blues addiction and study of the blues harmonica had begun – but not so much as a solo artist, more as the backing for the sinister yet amazing Sonny Boy Williamson. They worked together on the AFBF tours of 1963 and the resultant incredible Storyville recordings that were released in their best form on Alligator Records as “Keep It To Ourselves”. In perfect honesty, Slim’s performances didn’t stand out to me in comparison to Sonny Boy.

Sonny Boy’s schtick was two-fold. Firstly his “double-bluff” performance style of visually behaving like he didn’t care while actually performing music of high emotional impact focus and dedication.

Secondly his deliberate ploy of creating a knife edge tension between himself and the audience and the members of the band by quite obviously not having a set list and starting the song off on harmonica and expecting the highly accomplished musicians including Matt Guitar Murphy on guitar, Billy Stepney on drums and of course Slim on piano to fall in behind him by figuring out the key, rhythm and feel by the clues in his harmonica intros.

Whereas Sonny Boy deliberately toyed with chaos and relished a shady outsider personality, Slim’s music was all about precision, control, dignity and visible professionalism. He was aiming to be INSIDE the establishment.

Each song was well rehearsed, identically performed and as slick as could possibly be. I naturally gravitated towards the Sonny Boy approach.

But music aside – I wanted to know how Slim had managed to create such a success for himself in France, and so I started to interview many people, musicians, family members and business associates, who had known him and I also started to hunt down all available recordings.

The story, which is a fascinating one, is being developed into a long article. The more I learnt about his career, personality and the historical context of his music the more I began to understand his approach and both appreciate and enjoy his art and furthermore attempt to perform it.

One arch and condescending European commentator described Slim as “A vagrant, with the manners of a viscount”, another described his music as “Blues that knew how to behave”. He dressed like a doctor or a lawyer and his music was an ingenious and almost unique hybrid of earthy down-home blues with a steely, considered urbanity and a very slight jazzy sensibility.

On the piano, he played complex and detailed lines with his right hand over solid simple blues bass lines with his left and sang with the deliberate slight detachment of a professional man in control, but still hinted at the emotional distress beneath. He was a purveyor of working class American blues, but gentrified both the music and his own persona, giving himself a gateway into the upper echelons of Parisian society and music industry and was rewarded handsomely, playing both large theatres and small jazz clubs and having numerous appearances on national TV.

He also had the financial ace card of having written one of the most famous and successful blues songs of the twentieth century, “Everyday I Have The Blues”, and owning the copyright – providing him, in today’s money, with hundreds of thousands of euros per year in publishing royalties.

His vast recorded output is varied and ranges between attempts at pop success, solo albums of traditional blues aimed at the folk market and his incredible fifties RnB work on United and VeeJay. But my great discovery was everything and anything he recorded and filmed with just the great French drummer Michel Denis.

Here everything came together in a unique blues jazz hybrid that was designed for silent and seated European audiences in large theatres or tiny jazz and blues clubs. The jazz-orientated drums not only grooved – they picked out the detail of Slim’s filigree playing and arrangements and both Slim and Denis had a back and forth musical conversation rich with witty non-verbal musical humour and dynamics.

During my series of interviews for the essay I struck up a great rapport with the incredible French pianist Philippe LeJeune who, having been very close personal friends with Slim and having recorded an album with both Slim and Michel Denis in the eighties called “Dialog In Boogie”, gave me some incredible insights into the man and the music.

As my appreciation of Slim grew I started to copy some of his lines on my harmonica and also incorporate some of his songs and showmanship techniques into my set. I had also starting researching The Left Bank of Paris and the clubs Slim played – most of which still exist.

The idea came to me to collaborate with Philippe on a tribute show and so “When Paris Met The Blues” was born.

And so I’m proud to present the booking trailer for “When Paris Met The Blues”. And for me, who did most of this work and research during lockdown – I look forward to meeting Paris again and playing some blues for Memphis Slim in the beautiful city of lights, when things return to normality!

Visit Giles’ website for news of his upcoming gigs and to order his album, For Those Who Need The Blues