I’m not the only music fan who developed a fascination for certain record labels. Not the majors, of course, they can look after themselves, but it’s a special feeling to adopt a small, independent label, preferably one who wears its musical heart on its sleeve.

One of my favourites was, and still is, the tiny Sue Records, originally from Lafayette, Louisiana, but licensed to Island Records in London who muddied the water somewhat by putting recordings from other U.S. independents onto Sue for the UK, which was reportedly outside their agreement and led to a bust-up and talk of litigation. The behind-the-scenes kerfuffle didn’t affect the record-buyer, who sought out the distinctive red and yellow label which carried such names as Huey Piano Smith and The Clowns (they hit in 1957 with “Rocking Pneumonia and The Boogie Woogie Flu”), trombone ace Harold Betters, early Ike and Tina Turner, Bob and Earl with their dance classic “Harlem Shuffle”, Wilbert Harrison, Jimmy McGriff and, importantly, The Phil Upchurch Combo with their single “You Can’t Sit Down” parts One and Two on either side of the 45.

Throughout the 1990s Big Bear was responsible for booking the bands into Ronnie Scotts club in Birmingham, affording us the unique opportunity to bring in the sort of bands that otherwise would never be heard in this city. Predictably, the star of Sue Records, The Phil Upchurch Combo, loomed large on that list.

We booked Upchurch to play a week at the Broad Street club. This was their only ever UK appearance, attracted audiences from throughout the UK and left the club’s owners, who had never previously heard of him, chortling over their takings.

The opening night was a killer, with Upchurch delivering all that the capacity audience had come to hear – and rather more. The surprise package was the piano player.

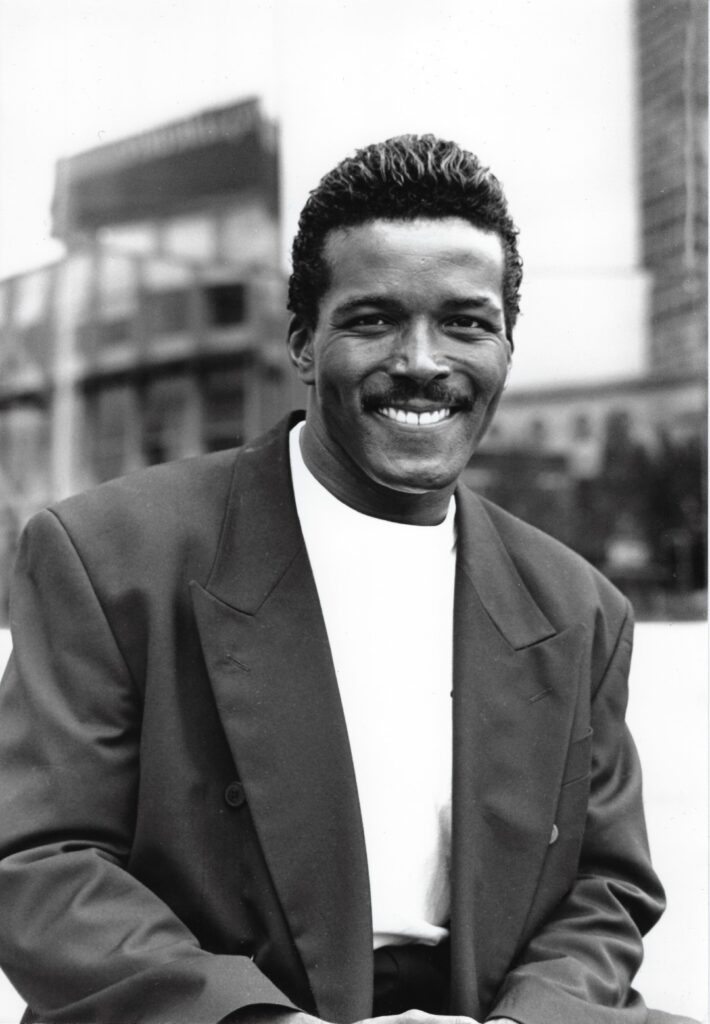

He was tremendous throughout, until he sang and then he was even better, with his feature spots the highlight of the show. His name was Howard McCrary, born in Youngstown, Ohio, one of eight boys in a family of ten children. To my embarrassment I had never before heard of him. Word spread quickly, and by the end of the week, audiences were clamouring for more of that blues-soaked McCrary voice and down-home piano playing.

I spent a lot of time with Howard that week, initially floored to learn that he actually knew little about the great bluesmen and realising that he was simply a blues natural who had got to where he was without consciously being influenced by other singers.

We spent our downtime that week delving into my record collection, and I’ll never forget his delight when he first listened to the recordings of Jimmy Rushing, Ernie Andrews, Joe Williams, Charles Brown [in particular], Willie Mabon, Walter Brown and the like.

The week at Ronnie’s ended. On the Sunday morning I waved the Upchurch Band off as they headed to the airport to fly to Amsterdam for the final date of the European tour, Howard and I agreeing to stay in touch and do something together in the future.

Early on the Monday, I was in the office when I got a call from Howard who I had thought would be on the flight back to L.A. I asked where he was and he replied “I’m at the airport.” I asked if the flight was delayed and why was he still at Schiphol and his response floored me, “I’m in Birmingham – the guys have flown home, but I decided to come back to Birmingham so we can work together.”

So he moved in with me and stayed until I could fix him a flat and piano. I then put the arm on the Ronnie Scotts owners to book him to play a late show, six nights a week from midnight until 2am which I called “The Midnight Slows”. He went to work on the following Friday and the word quickly spread. Some of the audiences from the evening show stayed on while new audiences, predominantly female, arrived just for Howard who simply played solo piano, sang the blues and was stunning.

In response to his request, I put together a cassette of a dozen or so blues recordings to suggest the type of material he might like to consider and to my amazement, within 48 hours, he had nailed every single one of the songs – lyric, melody, chords, the lot, and more than that, he was delivering them as his, in his own very personal style. It became apparent that there was a growing number of gospel fans in his audience, and I learned that the McCrary name is well known in the world of U.S. gospel music.

He had told me that he had learned to sing in church, but I had no idea how important the McCrary Family Choir were, nor the McCrary Five, featuring Howard, who had toured coast-to-coast, double-headlining with The Jackson Five. There was much more that the ever-modest McCrary hadn’t bothered to mention. He had been a member of The California Raisins, befriended Michael Jackson and worked with him in the recording studio and with Quincy Jones, who had gone on to produce Howard himself.

Howard had worked as musical director on recordings by Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Julio Iglesias, Nina Simone, Ringo Starr, Dionne Warwick, Earth, Wind and Five and Chaka Khan – whose sister, Tammy, he married.

We got to work, firstly putting together his band of crack Birmingham musicians, Mike Burney on tenor, Josh McCalla on guitar, Roger Inniss on bass guitar and drummer Tim Jones. The McCrary Band quickly became regulars at Ronnie Scotts and were soon headlining and selling out full weeks. McCrary’s reputation had spread like wildfire and it was not difficult to put together a solid datesheet, first in the UK and then in Europe.

Major brewing company Mitchells & Butler sponsored a national 40 date tour of their bigger pubs, Howard was on radio and in the papers, and importantly to Big Bear, we had recorded a live album at Ronnie Scotts that captured McCrary and his band in full flight. Importantly, Mike Burney was on fire that night, at his majestic best.

This might just be the finest example of that remarkable musician’s work which is more poignant now that he has passed. After some 18 months here, McCrary’s love affair with Birmingham jolted to a sudden halt. His wife, Tammy, came to visit and naturally took over the reins of managing him. She soon decided that she didn’t really approve of his friends, who were predominantly young, female and nuts about Howard. Tammy took Howard by the ear back to L.A. leaving many a Brummie heart broken.

We lost touch for a while, until Julian Smith, he of Britain’s Got Talent fame now a star attraction on upmarket cruise ships, found himself on a several day stop-over between cruises, in Hong Kong. Visiting a club, he was surprised to see that the ever-youthful McCrary was the featured artist and got into conversation. Howard asked to be put back in touch with Big Bear, a direct result of which was the album that had been on the shelf since 1993 seeing the light of day some 25 years after it was recorded.

Sadly, both Josh McCalla and Mike Burney had passed away, but Howard, divorced from Tammy, is now happily married to Ivy Chang and he is the star of the Hong Kong music scene, regularly on TV and radio and hoping that the Covid situation lightens sufficiently to allow him to come to the UK this summer, visit his daughter who lives in London, and ……watch this space. You’ll be the first to know.

Howard McCrary’s album on Big Bear, ‘Moments Like This’, recorded live at Ronnie Scotts Birmingham is available to purchase and stream from the Big Bear website.